You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Ex-Wolf Watch

- Thread starter Deutsch Wolf

- Start date

Lupo

Well-known member

- Joined

- Apr 1, 2012

- Messages

- 8,646

- Reaction score

- 5,667

The plight of the unemployed manager is a curious phenomenon, one that lurches from loss to loneliness and quite often a long, hopeless struggle to get back in. It can last forever, or for no time at all, but it is always challenging and usually it begins with a sacking.

Mark McGhee has been dismissed frequently enough to know it shouldn’t be taken personally, but he will never forget the first time. After four uninterrupted years as the manager of Reading and then Leicester City, his three years at Wolverhampton Wanderers came to an abrupt end when, after successive failures to win promotion, he presided over just two wins in 12 matches.

First, there was the meeting at which he was told to pack his bags, then there was the introduction to “real life” for the first time in his long career as a manager and player. But what McGhee remembers most is the feeling a few days later when he saw first-hand that Wolves would carry on perfectly well without him.

“The following week, I got a phone call from big Mick [McCarthy] who was the Republic of Ireland’s manager at the time,” McGhee says. “He asked me to go to a game at Blackburn, watch the Irishmen who were playing and send him a report. He was doing me a favour really, getting me out of the house and keeping me involved.

“So that was great. But in order to go from where I lived, out near Bridgnorth, to the motorway, I had to drive on the stretch of dual carriageway that goes behind Molineux. And when I drove past, there was a game on, an early kickoff presumably. It actually brought tears to my eyes. Literally a week earlier, I had been king of the castle down there. And here I was, driving along, with it all going on in my absence. It was so emotional.”

This, then, is how it feels for former managers: sad, dispiriting and a little surreal. The sudden jolt from an all-consuming, 24/7 obsession with who to pick and how to make the team better is replaced the following morning by walking the dog and watching Homes under the Hammer.

It’s alright for José Mourinho, who is thought to have received £82m in compensation over the years. McGhee feels for managers further down the food chain who wonder if they can afford to keep chasing the dream. “They have not accrued vast amounts of money. They need to pay the mortgage and feed their families. Some of these young guys go straight into management, lose their job and suddenly they’re out on the street. It can be brutal.”

Deutsch Wolf

Sponsored by Amazon Prime. DM me for discounts...

- Joined

- Oct 16, 2009

- Messages

- 113,179

- Reaction score

- 43,710

Deutsch Wolf

Sponsored by Amazon Prime. DM me for discounts...

- Joined

- Oct 16, 2009

- Messages

- 113,179

- Reaction score

- 43,710

Nah, we've not done the Saturday afternoon reserve games at home since the mid 80s at very latest

He's a big fibber

He's a big fibber

Lupo

Well-known member

- Joined

- Apr 1, 2012

- Messages

- 8,646

- Reaction score

- 5,667

I was assuming it was an evening game but having re-read it suggests early KO at the weekend, yesNah, we've not done the Saturday afternoon reserve games at home since the mid 80s at very latest

He's a big fibber

Deutsch Wolf

Sponsored by Amazon Prime. DM me for discounts...

- Joined

- Oct 16, 2009

- Messages

- 113,179

- Reaction score

- 43,710

I could never pull off the cravat look like Fred.

Such a weird thing to lie about though. It also isn't an optimum route onto the M6 from Bridgnorth

Such a weird thing to lie about though. It also isn't an optimum route onto the M6 from Bridgnorth

Deutsch Wolf

Sponsored by Amazon Prime. DM me for discounts...

- Joined

- Oct 16, 2009

- Messages

- 113,179

- Reaction score

- 43,710

Mick is very bad with stuff like that. If he's recollecting his Wolves days he'll merge three different seasons into one anecdote which can't possibly have happened.

Deutsch Wolf

Sponsored by Amazon Prime. DM me for discounts...

- Joined

- Oct 16, 2009

- Messages

- 113,179

- Reaction score

- 43,710

Here's an odd one. Merseyside Police seemingly did their own Tranmere Rovers football cards in the 90s! And Thommo got one.

AndyWolves

Well-known member

- Joined

- Oct 28, 2010

- Messages

- 18,350

- Reaction score

- 8,855

"king of the castle"?

Really?

Really?

Wilf Wolf

Well-known member

- Joined

- Mar 12, 2011

- Messages

- 7,938

- Reaction score

- 5,892

The closest he gets is Peter Kay’s bouncy castle with Sammy Snake. In fact forget Sammy, McGhee was just a giant cock, much like Sammy."king of the castle"?

Really?

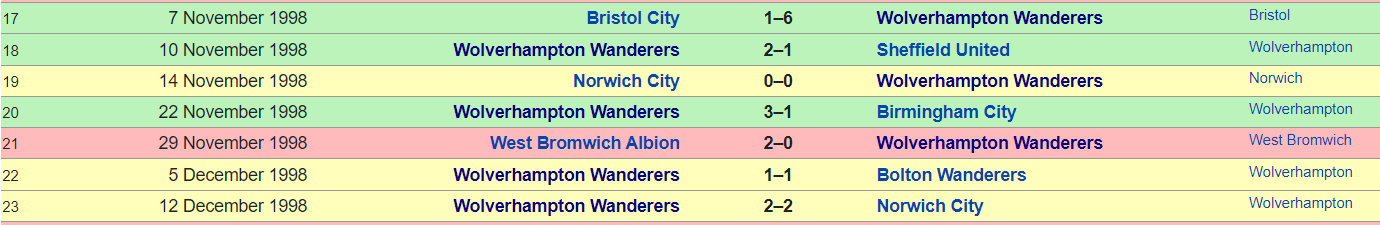

He also doesn't need to go anywhere near Wolverhampton, especially the ground, to get to Blackburn from Bridgnorth.I don't think that's true about him driving past Molineux and seeing an early game, the only one that fits the bill is Blues which *might* have been a Sunday lunchtime (I can't remember now) but Blackburn didn't play that day. The others were midweek (Sheff Utd) or Saturday 3pms.

View attachment 11385

Johnny75

Virtual Cock

- Joined

- Oct 24, 2011

- Messages

- 36,291

- Reaction score

- 12,474

My guess is that's what it was.Unless he was referring to the M54 when he said dual carriageway

AndyWolves

Well-known member

- Joined

- Oct 28, 2010

- Messages

- 18,350

- Reaction score

- 8,855

Always thought Moulden was decent

Jack Regan

Hodor. Hodor? HOOODOOOOR!

- Joined

- Feb 4, 2010

- Messages

- 10,636

- Reaction score

- 4,228

He's 22 years old why the hell are Palace academy tweeting it?