28th December

1879 –

Tay Bridge disaster: The central part of the

Tay Rail Bridge in

Dundee, Scotland, United Kingdom collapses as a train passes over it, killing 75.

On the evening of Sunday 28 December 1879, a

violent storm was blowing virtually at right angles to the bridge. Witnesses said the storm was as bad as any they had seen in the 20–30 years they had lived in the area; one called it a '

hurricane', as bad as a typhoon he had experienced in the

China Sea. The wind speed was measured at

Glasgow and

Aberdeen at 71 mph.

Higher windspeeds were recorded over shorter intervals, but at the inquiry an

expert witness warned of their unreliability and declined to estimate conditions at Dundee from readings taken elsewhere. One modern interpretation of available information suggests winds were gusting to 80 mph.

Use of the Tay Rail Bridge was restricted to one train at a time by a

signalling block system using a baton as a

token. At 7:13 p.m. a

North British Railway passenger train from

Burntisland, consisting of a

4-4-0 locomotive, its

tender, five passenger carriages, and a luggage van slowed to pick up the baton from the signal cabin at the south end of the bridge, then headed out onto the bridge, picking up speed.

The

signalman turned away to log this and then tended a stove, but a friend present in the

signal cabin watched the train: when it got about 200 yards from the cabin he saw sparks flying from the wheels on the east side. He had also seen this on the previous train. During the inquiry, testimony was heard that the wind was pushing the

wheel flanges into contact with the running rail. John Black, a passenger on the previous train that crossed the bridge, explained that the guard rails protecting against

derailment were slightly higher than and inboard of the running rails. This arrangement would catch the good wheel where derailment was by disintegration of a wheel, which was a real risk before steel wheels, and had occurred in the

Shipton-on-Cherwell train crash on Christmas Eve 1874.

The sparks continued for no more than three minutes, by which time the train was in the high girders. At that point "there was a sudden bright flash of light, and in an instant there was total darkness, the tail lamps of the train, the sparks and the flash of light all ... disappearing at the same instant." The signalman saw none of this and did not believe it when told. When the train failed to appear on the line off the bridge into Dundee he tried to talk to the signal cabin at the north end of the bridge, but found that all communication with it had been lost.

Not only was the train in the river, but so were the high girders and much of the ironwork of their supporting piers.

[note 2] Divers exploring the wreckage later found the train still within the girders, with the engine in the fifth span of the southern 5-span division.

[19] There were no survivors; only 46 bodies were recovered out of 59 known victims.

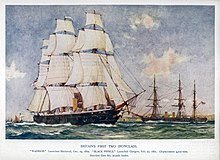

The bridge had been designed by

Sir Thomas Bouch using

lattice girders supported by iron

piers, with

cast iron columns and

wrought iron cross-bracing.

Bouch had sought expert advice on

wind loading when designing a proposed rail bridge over the

Firth of Forth; as a result of that advice he had made no explicit allowance for wind loading in the design of the Tay Bridge. There were other flaws in detailed design, in maintenance, and in quality control of castings, all of which were, at least in part, Bouch's responsibility.

Bouch died less than a year after the disaster, his reputation ruined.